Benchmark of Popular Reinforcement Learning Algorithms

Deep-learning ·This post is a reflection of my study through OpenAI’s tutorial, Spinningup, of deep reinforcement learning. It mainly covers six popular algorithms including Vanilla Policy Gradient (VPG), Trust Region Policy Optimization (TRPO), Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient (DDPG), Twin Delayed DDPG (TD3) and Soft Actor-Critic (SAC). I have implemented all these algorithms under the guidance of the tutorial. I would like to highlight the key ideas and critical theory behind each algorithm in this post. Meanwhile, I will also share the benchmark performance of these algorithms using my own implementation.

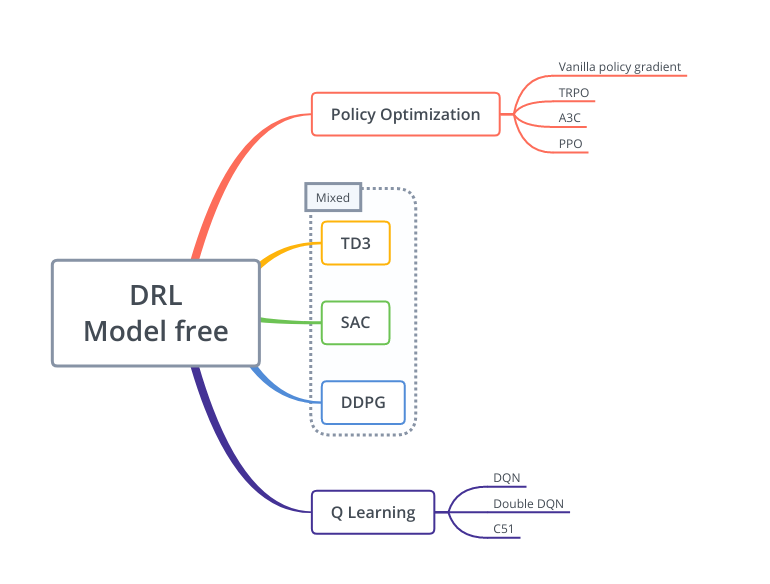

The figure below shows the category of all the presentated algorithms. They all belongs to model free RL algorithms, since they do not explicitly learn a model or have access to the environment model.

Policy Optimization:

- directly optimizes the performance of the policy, either explicitly using policy gradient, or modifying policy gradient for the sake of stability and efficientcy.

- normally belongs to actor-acritic structure

- usually runs in on-policy

- stable and reliable training as directly optimizing what we want

Q Learning:

- also called value learning methods;

-

implicitly finds optimal policy through learning action value or value function to match Bellman equation. Optimal actions are computed through optimal Q function: \(a^* = \arg\max Q^*(s,a)\)

- almost always runs in off-policy

- less stable training in practice

- higher sample efficiency when it works

The mixed algorithms (TD3, SAC, DDPG) lie between these two approches.

Vanilla Policy Gradient

This algorithm is the basic policy gradient version, which is also called REINFORCE. The concept is quite simple and direct. Aiming to maximize the discounted return \(J = \max_{\tau \sim \pi} E(R(\tau))\), this method explicitly update the policy with the gradient of the cost function. The policy gradient has a beautiful format which can be easily deducted using some basic math knowledge. Here is the policy gradient:

\[g = E_{\tau \sim \pi_\theta} [\sum_{t=0}^{t=T} \nabla \log \pi_\theta(a|s) R(\tau)]\]which is easy to remember as Exp-Grad-Log. This analytical format can be estimated by sampling trajectories at policy \(\pi_\theta\). It ends up with the numerical calculation format as: \begin{equation} \hat{g} = \frac{1}{\mathcal{D}} \sum_{\tau \sim \mathcal{D}} \sum \nabla_\theta \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s) R(\tau) \label{eq:grad} \end{equation}

There are two important variations based on \eqref{eq:grad}, which can imporove the learning process.

- Rewards-to-go \begin{equation} \hat{g} = \frac{1}{\mathcal{D}} \sum_{\tau \sim \mathcal{D}} \sum \nabla_\theta \log \pi_{\theta}(a|s) \underline{R_t(\tau)} \label{eq:r-to-go} \end{equation}

Instead of using the complete return \(R(\tau)\), we replace it with the rewards-to-go term:

\[\begin{equation*} R_t(\tau) = \sum_{t=t'}^{T} r_t, \end{equation*}\]this term makes the policy forget the previous rewards, which benifits it by not stucking at old rewards.

- Advantage (Highly preferred in practice!)

Advantage means that how much better it is to take a certain action, over randomly selecting actions on a state. It is a relative comparison compared with the absolute return by accumulating rewards.

\[\begin{equation} A(s_t, a_t) = Q(a_t, s_t) - V(s_t). \label{eq:adv} \end{equation}\]In practice, \(A(s_t, a_t)\) is not known. GAE gives an accurate estimate of the advantage in a nice mathematical formula:

\[\begin{equation*} A_t(s_t, a_t) = \sum_{c=0}^{inf} (\gamma \lambda)^c (r_{t+c}+\gamma V(s_{t+c+1}) - V(s_{t+c})) \end{equation*}\]where \(\lambda\) is close to 1 for the best trade-off of varaince and bias.

There is a fast implementation to compute a sequence of advantage along timesteps,

def cum_discounted_sum(self, x, discount):

"""

Magic formula to compute cummunated sum of discounted value (Faster)

Input: x = [x1, x2, x3]

Output: x1+discount*x2+discount^2*x3, x2+discount*x3, x3

"""

return scipy.signal.lfilter([1], [1, float(-discount)], x[::-1], axis=0)[::-1]

This is the fastest implementation as I know compared with the other ways, like the forward computation and the diagnal matrix assignment.

Trust Region Policy Optimization

TRPO can be regarded as a strengthen version of VPG, which aims to take the maximimal gradient step without driving away too much from the previous policy. A main feature of TRPO is that it optimizes the relative improvement of the policy performance, which is modelled in a surrogate advantage \(J(\theta_k, \theta) = E[\frac{\pi_\theta}{\pi_{\theta_k}} A^{\theta_k}]\). The updated policy is constraint with the KL-divergence:

\[D_{KL}(\theta || \theta_k) = E(D_{KL}(\pi_\theta(\cdot|s) || \pi_{\theta_k}(\cdot|s))) \leq \delta\]where \(\theta_k\) is the old policy parameters.

Using Taylor expansion and Lagrangian duality methods, the analytical solution of the optimization problem is:

\[\begin{equation} \theta_{k+1} = \theta_k + \sqrt{\frac{2\delta}{g^T H^{-1} g}} H^{-1}g \label{eq:npg} \end{equation}\]where \(H\) is the hession matrix of \(D_{kl}\) and \(g\) is the gradient of \(J\).

\eqref{eq:npg} is called Natural Policy Gradient. However, due to to approximation error of Taylor expansions, this solution can violate the KL-divergence constraint. Therefore, we search the largest step we can take within the constraint \(\alpha^j \sqrt{\frac{2\delta}{g^T H^{-1} g}} H^{-1}g\), which is equivalent to find the smallest j without breaking the constraint.

It is notorious that computing inverse of hession matrix is expansive and numerically unstable. The conjugate gradient is specifically used to solve this problem. We try to solve \(Hx=g\), with \(x=H^{-1}g\).

def conjugate_grad(Hx, g):

"""

Conjugate gradient method

Given Hx = g, return x

start with initial guess x0 = 0

"""

x = np.zeros_like(g)

r = g.copy()

p = g.copy()

rr = np.dot(r, r)

for i in range(cg_itr):

z = Hx(p)

alpha = rr / (np.dot(p, z)+EPS)

x += alpha*p

r -= alpha*z

rr_new = np.dot(r, r)

beta = rr_new/rr

p = r+beta*p

rr = rr_new

return x

Proximal Policy Optimization

PPO tries to solve the same problem as TRPO using the first order method instead of computing the second order Hessian matrix. The cost function is reshaped to put boundaries over the proportion between the new policy distrition and the old policy distribution,

\[\begin{equation} J(s, a, \theta_k, \theta) = \min \Big(\frac{\pi_\theta(a|s)}{\pi_{\theta_k}(a|s)} A^{\pi_{\theta_k}}, clip(\frac{\pi_\theta(a|s)}{\pi_{\theta_k}(a|s)}, 1-\epsilon, 1+\epsilon) A^{\pi_{\theta_k}} \Big). \label{eq:ppo} \end{equation}\]- When advantage is positive, we would like to increase this action probability in order to reach a higher return.

The clip and min operations are utilized to limit the increasement by putting a ceiling of \(1+\epsilon\). Therefore, the new policy doesn’t drive too far away from the old policy.

- When advantage is negative, we would like to decrease this action probability in order to reach a higher return.

The clip and max opeartions limit decreasement by putting a floor of \(1-\epsilon\). Therefore, the new policy doesn’t drive too far away from the old policy.

Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient

DDPG is close to the idea of DQN. However, it trains a policy network to maximize the expected return (not exactly but similar) which is estimated as state-action pair values in a Q network. The Q network is updated based on the Bellman equation. In order to stabilize the learning process, an important idea is propsed, called target networks. For both policy network and Q network, each has a twin-like target network, which can be regarded as a delayed version. In practice, we can use tf.variable_scope() to seperate the parameters between the two networks, such as

with tf.variable_scope("main"):

pi, q, q_pi = actor_critic_fn(s, a, act_space, hid, hid)

with tf.variable_scope("targ"):

pi_targ, _, q_targ = actor_critic_fn(s, a, act_space, hid, hid)

Eventually, we still use the main networks for inference.

Another difference of DDPG is that it runs in off-policy, which indicates we will have a large replay buffer to collect all transactions with a reasonable forgetting rate. Meanwhile,, we usually randomly sample or use priority to sample minibatch from the buffer to alleviate the non-stationary of experiences.

Twin Delayed DDPG

DDPG is prone to overestimate the Q values. TD3 solves this problem through three tricks:

- Twin

Instead of one target Q network, here comes two Q networks. And the smaller one is used to compute the target.

- Delayed

TD3 updates the target networks and policy network less frequently in order to to add some damping.

- Target policy smoothing

Add noise for the target action

Soft Actor-Critic

SAC extents the DDPG-style learning to the stochastic policy. The main feature is to introduce the entropy regularization in the cost function. The policy is trained to balance between the expected return and policy entropy. Higher entropy will increase the exploration and avoid the local optimum. The optimal policy in entropy-regularized reinforcement learning resultes in:

\[\begin{equation*} \pi^* = \arg \max E\Big[ \sum \gamma^t (R(s_t, a_t, s_{t+1}) + \alpha H(\pi(\cdot|s_t))) \Big] \end{equation*}\]\(\alpha\) controls how much exploration you want, normally it is small like 0.1. In Q and V functions, all the rewards term are extented with the entropy term.

The whole story of SAC is more complicated and requires deeper math knowledge. In general, it trains two Q function, one V function and one policy function.